|

The Sentinel

Society has no truer mirror than its advertising.

Society has no truer mirror than its advertising.

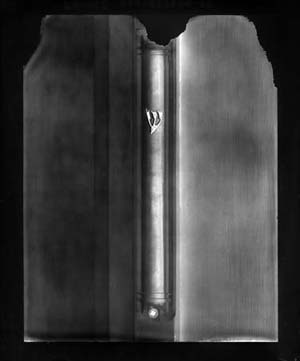

What motivates people to put their hands in their pockets and pull out their hard-earned cash must appeal to their innermost desires. And what someone wants, what he truly desires - is who he is. Think, for a moment, of all those car ads filmed in the desert. There's no one for fifty miles in any direction. Climb behind the wheel and you can go wherever you want, whenever you want. You can be whatever you want. Think of all those ads for away-from-it-all vacations (whatever the dreaded "it" might be). They all express the same ideal: the commitment to being uncommitted, the freedom to do what I want when I want, and to change what I want from one moment to the next. Society pays lip service to the ideals of commitment, stability, and fidelity. Advertising, however, gives the lie to that sanctimony and reveals that society's real aspiration is to be free to "go with the flow." Unfortunately, modern secular man finds his flow severely restricted. At every turn, he is encumbered by commitments: a home, a wife, children, a mortgage, a second mortgage, a second wife. What he would really like to do is take off and travel the world with a credit card and unlimited credit - to follow any, or all, of a myriad of possibilities. The fact that he tolerates responsibility doesn't mean that he has accepted a specific form and purpose to his life. He'd really like to be somewhere else, anywhere else, everywhere else. From where does this ideology of irresponsibility come? Is this desire for constant change a new phenomenon, or does it have its roots in something much more ancient? Everything in this world is a combination of matter and form. By definition, matter has no form. It has an infinite number of latent forms, of different shapes. Matter, ungarbed by form, has unlimited potential uses. In a world that is all matter, everything is possible. Nothing is fixed. You can "go with the flow." The epitome of matter is water. Water always takes the form of its container. Itself, it has no shape, no form. For that reason the Hebrew word for "water," mayim, is a plural noun. There is nothing singular about the shape of water. It has an infinite number of shapes. Water, in the "shape" of the Nile, was the idolatry of the Egyptians - for if ever there was a society that epitomized unbridled matter it was Egypt (Yechezkel 23:20). Egypt was an entire society dedicated to the pursuit of infinite variety and potential. By definition, such a society is incapable of, and scorns, marital fidelity. Egypt was the "eishet zenunim" - the unfaithful wife, the antithesis of Shlomo HaMelech's eishet chayil, the Jewish woman of valor. Egypt was the faithless spouse who seeks constantly a new partner, a new form. Inconstant as water, she wants to "go with the flow." In diametrical opposition to this culture stands the Jewish home. The spiritual masters refer to a wife as "home." The Jewish home represents the ultimate triumph of matter that is forever faithful, for the eishet chayil, the woman of valor, is able to concretize incessant potential and give it unchanging stability. The cornerstone of our belief in God's constant involvement and guidance of the world is the Exodus from Egypt. One of the ways that we internalize this belief throughout the generations is by fixing a mezuza to our doorposts. In the two paragraphs of the Torah that constitute the mezuza, however, you will find not one word about the Exodus. If the job of the mezuza is to implant in us a steadfast faith in the miracles of Egypt, shouldn't the Exodus be mentioned in it at least once? When the Jewish people were about to leave Egypt, God commanded them to place the blood of the Pesach offering on their doorposts and lintels. The word pesach comes from the root "to skip over" or "to leap." As the Torah teaches (Shemot 12:23), God (so to speak) "leaped over," or "passed over," the entrances of the Jewish homes in Egypt. The Exodus from Egypt was not merely a physical exodus. It was no less than a leap from one world to another - a leap from a world of matter to a world of form. And ironically, inevitably, this leap had to take place while the Jewish people were immobilized in their homes: "And you may not leave your house until morning" (Shemot 12:22). The metamorphosis from matter to form, which was the essence of the Exodus, took place specifically when they had to stay in the place that is the essence of form, the Jewish home. What is left of the blood of the Pesach offering on our doorways in Egypt is the mezuza. The mezuza is the pesach - the leap that is in essence the Exodus from Egypt. The mezuza does not speak about the Exodus, for it is the Exodus itself. The mezuza marks the border between "the street" and the home. The street says, "Go here! Go there! All things are possible. Nothing is fixed. Go with the flow!" The mezuza stands like a sentinel at the threshold and states unequivocally that there is no connection between the street and the home. Silently, it proclaims that they are two noncontiguous, irreconcilable entities. On the outside of every mezuza are inscribed the letters shin, dalet, and yud. These letters spell one of God's Names: Sha-dai. Unroll the mezuza, and in that self-same place where that Name appears, but on the reverse side, is written another of God's Names, the ineffable Name of four letters -Yud and Heh and Vav and Heh. The name Sha-dai means "the One who said to the world 'Enough!' " (Bereishit 30:5; Chagiga 12a). When God created the world, He did it in such a way that the Creation would have been continuous and unceasing. It would have gone on and on, expanding forever. However, the Infinite Wisdom decreed that the Creation be contained, limited. God said, "Dai - Enough!" Creation should go this far and no further. Why are these two Names of God juxtaposed on the two sides of the mezuza? According to Jewish law, the reshut harabim, the public domain, ascends vertically only to approximately three feet above the ground. Horizontally, it can extend everywhere, all over the world, but it never ascends. The street is trapped within the confines of this world. The reshut hayachid, the private domain, on the other hand, has no upper limit. In the home, the sky is the limit. That is where the ineffable Name, Yud and Heh and Vav and Heh, is revealed. It is in the home that a person can ascend heavenward. However, our ascent upwards is proportionate to our limitation outwards. That is why Sha-dai is on the outside of the mezuza, while on the inside is Yud and Heh and Vav and Heh, the Name that has no restrictions. The mezuza tells us that if we say, "Dai! Enough!" to the street, if we make a strong demarcation between all that the street stands for and the sanctity of the home, then inside, God's ineffable Name, the Name of Yud and Heh and Vav and Heh, can illuminate our homes and our lives. A LEAP OF FAITH

in the small box at the gateway sits the sentry unfailing in his vigilance he will ask you questions that you cannot answer, like, how big is space? how large is a place? how can you get here from there with just a leap of faith? More articles available at Ohr Somayach's website. |